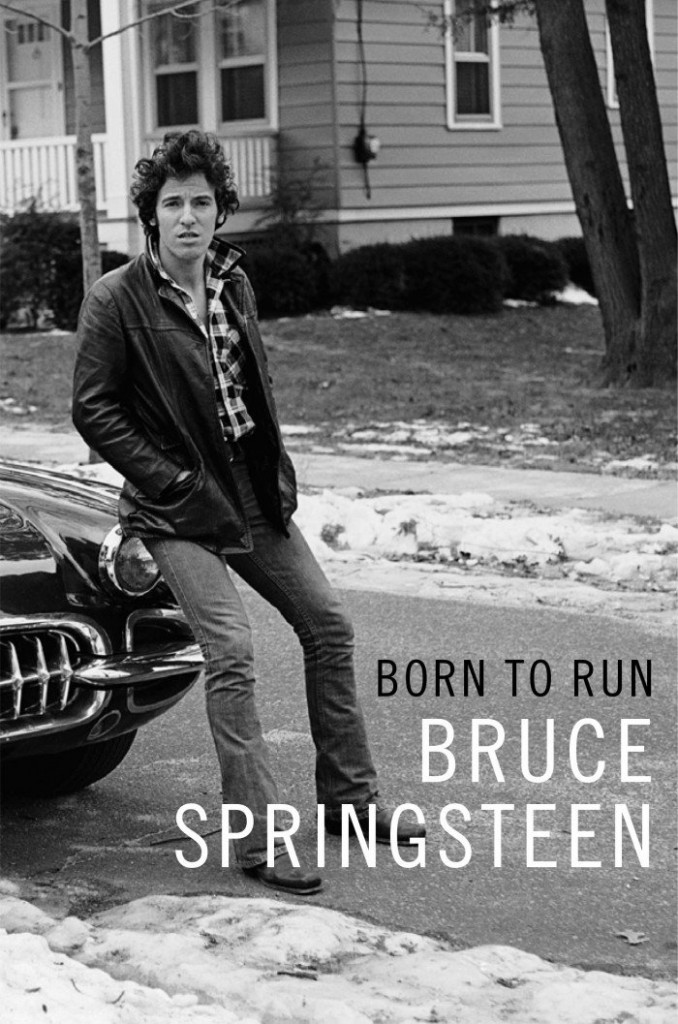

Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run”

Bruce Springsteen did not go to NSCAD. This is a fact I gleaned from reading the New Jersey icon’s recent best-selling memoir, Born To Run.

Bruce Springsteen did not go to NSCAD. This is a fact I gleaned from reading the New Jersey icon’s recent best-selling memoir, Born To Run.

I’m stating this because (a) when I taught film history there, from 1986 to 2001, there was a persistent rumour that “The Boss” attended the local art college sometime in the late 1960s and / or the early 1970s, around the time when The New York Times called the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design “the most important Art College in the world,” and (b) because I know Tim Bousquet at the Halifax Examiner always finds it amusing when I try to link famous people to Canada’s Ocean Playground.

In the real world, in 1974 critic and producer Jon Landau said of the young rocker from New Jersey, “I have seen the future of Rock and Roll and his name is Bruce Springsteen.” The next year, Springsteen landed on the cover of both Time and Newsweek.

It was a wave of hype hard to live down, and Springsteen didn’t hit the top until 1984’s epic chart-buster, Born In the USA album, and even then it was perhaps for all the wrong reasons. Mistaken as an emblem of the 1980s feel-good patriotic Americanisms that dominated during the Reagan era, much of Springsteen’s new mass audience missed his chronicling of the decline of the U.S. working and middle classes, preferring instead his “big rawk” sounds as a soundtrack to a rash, rather primitive American revivalism and nativism.

Of course, Springsteen was always something of a retro artist, delivering a look back rather than a look forward. His emergence came at the end of popular music’s expansionary cycle when the last of the North American baby boomers were being assimilated into the final sputterings of an expanding economy.

As told in Born to Run, Springsteen’s first album was a singer-songwriter set. His second referenced the style of Van Morrison, an artist still peaking and relevant in 1973 and 1974. But it was Springsteen’s seminal third disc, Born To Run, in 1975, that finally defined his sound and set him on his way to sales and fame.

For me it was an awkward and difficult record. Blending the huge cinematic sweep of sound pioneered by Phil Spector with turn-on-a-time dynamics, topped off by a fascination with teenage dramatics, Born To Run seemed impossibly exciting and hopelessly vulgar, sounding something like the aural equivalent of an elephant on roller skates: an impressive logistical achievement, but hardly sustainable or even very safe in practical terms.

It’s important to remember that Springsteen emerged in the mid-1970s when popular music, in North America at least, was already awash in nostalgia. Many of dominant artists of the time – Linda Ronstadt, Jefferson Starship, Peter Frampton, Paul McCartney, Steve Miller, Fleetwood Mac, Carole King – were already veterans of the 1960s. Several 1950s pop stars, such as Paul Anka and Neil Sedaka, topped the charts at the time with memorably awful material. Anka’s “You’re Having My Baby” is perhaps the worst example.

Springsteen hardly came across at the time as a nostalgia merchant, but his backward-looking sound always reflected a certain lack of vision in my opinion. In similar books, by the Kinks’ Ray Davies, for example, or fellow Jerseyite and punk poet Patti Smith, there is a feeling of revelation and insight; Bob Dylan’s tome Chronicles, for instance, sparkles with a visionary sensibility that reveals early 1960s New York City as a kind of cultural Valhalla.

Springsteen’s book seems devoid of such hosannas. Instead there is much ambition and tough clawing towards the goal of making a living in music. There are plenty of hard lessons, as band-mates get tossed, nameless girlfriends appear as pit-stops along the way, and friends are measured by how they can be used to build up a career, but what dominates is a drive to succeed, rather than any particular insight.

While the book disappoints in one way, it does cruise onward with an unstoppable sense of forward motion. There’s a powerful therapeutic reasoning behind Springsteen’s writing, as he tries to understand his father’s inarticulateness that rode the edge between the repression of the 1950s and the growing counterculture of the 1960s.

Echoing the actor and playwright Sam Shepard’s various portraits of the declining role of masculinity, Springsteen’s struggles with post-World War Two male heroism reach an interesting zenith as he describes how he and two other friends got out of their Vietnam-era draft notices. The choice between being a dead patriot and an alive, long-haired hippy musician was a pretty easy one to make if you could get away with it.

The bulk of Springsteen’s autobiography sees him trying to balance his domestic life against the pressures of churning out relevant popular art in a changing environment. When he changed course from time to time into folkish forms for albums such as The Ghost of Tom Joad and Nebraska, the rocker delivered an order of bleak with a side of despair, in contrast to his E-Street band’s Wagnerian bombast. It was on these albums that Springsteen managed to add some rural spice to his usual urban meat-and-potatoes musical menu.

In between various levels of success, the book details a battle with late-onset depression. It seems something of a sideshow to the main narrative of the music, but the tension involved does provide for a sense of ongoing drama.

At times, like in his artistic career, Springsteen strains for significance. I always preferred his throwaway pop material, like the stuff he wrote for the Pointer Sisters (“Fire”) and the two albums for old-school rocker Gary ‘US’ Bonds, where music is fun, disposable and untethered to stories about lost dreams and crummy economies. But Springsteen himself clearly wants to be taken seriously, hence the epic reach of the tome.

Still, Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run – the book rather than the album – is a gripping page-turner that rates as essential reading for any and all of his fans. Those interested in popular culture and autobiographies in general should find it both satisfying and illuminating. I certainly did… even if “The Boss” never attended NSCAD.

Ron Foley Macdonald

Latest posts by Ron Foley Macdonald (see all)

- Mary Tyler Moore in Nova Scotia - January 30, 2017

- Viola Desmond’s Story on Film - December 11, 2016

- Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” - December 9, 2016