Gregor Ash… Unplugged

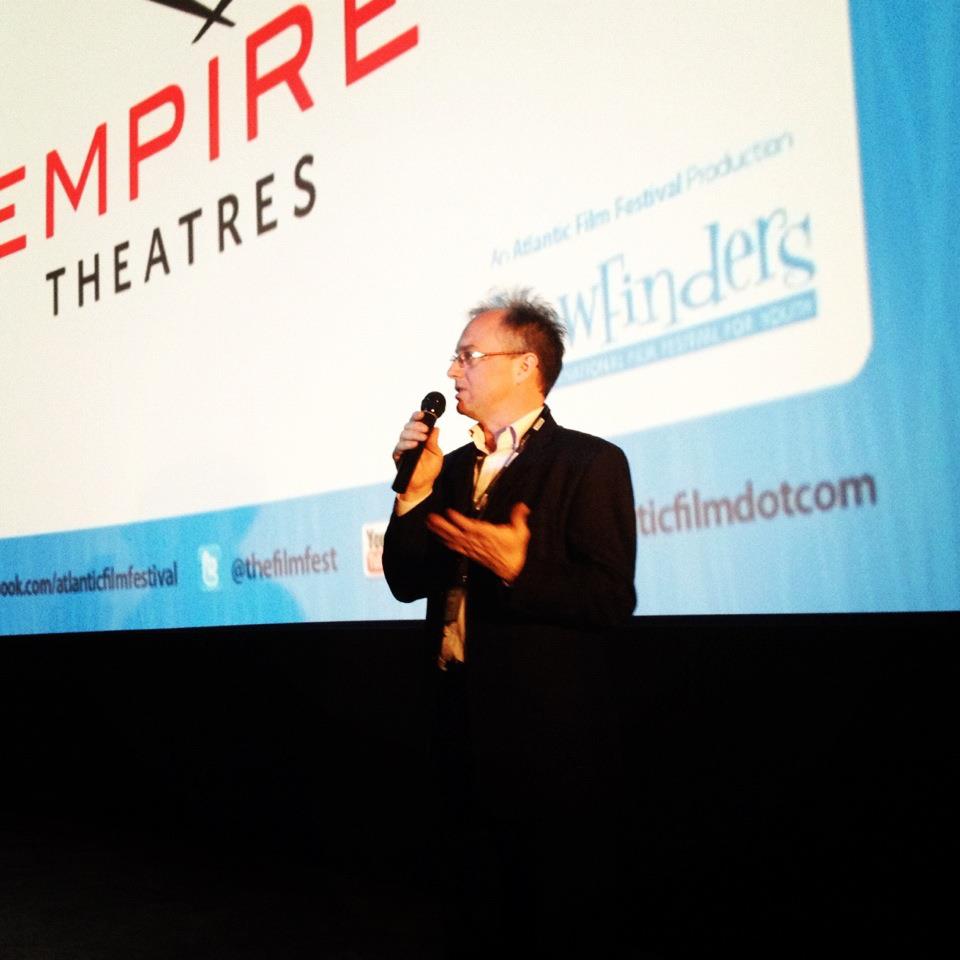

If you had to compile a list of the twenty most important and / or influential people in the arts and culture scene in Nova Scotia over the past fifteen years, it would probably include Gregor Ash. Starting from his first arts gig as sales and promotion manager at CKDU radio in 1991 – 1992 through his various key roles in the music industry at the height of the Halifax Pop Explosion to his tenure at the Atlantic Film Festival, first as Operations Manager from 1996 until 2000 and then as the very forward-looking Executive Director of the Festival from 2000 until 2012, Gregor was on the front lines of what was a true Renaissance period for film and music in the province. He has also served as a member of the Nova Scotia Arts & Culture Partnership Council in 2010 – 2011, and as the Director of the Institute of Applied Creativity at NSCAD University from 2012 until 2014. A two time candidate for elected office as a New Democrat (federally in 2011 and provincially in 2013), Gregor currently runs his own independent consultancy firm. I’ve known him since he was at the Film Festival and I was the Program Administrator at the Nova Scotia Film Development Corporation, and I’ve always had a great deal of respect for his commitment to the arts specifically, and public policy in general. He describes himself on Twitter as “a passionate servant of the Arts, a political junkie, a food lover and proud Newfoundlander, living a content life in the wonderful city of Halifax, Nova Scotia,” and I think that pegs him pretty much spot on. In an industry full of poseurs and provocateurs (and that applies to both the arts and politics), Gregor is genuine,passionate, and hard-working.

I asked him a couple of weeks ago if he would be willing to sit down and discuss his career in the arts and politics to date, and he readily agreed. We finally managed to sync our schedules for Friday afternoon, the 26th of February, and we got together at the Second Cup in the Killam Library at Dalhousie for a wide-ranging conversation about arts, culture, the creative economy, and politics. We had actually been chatting for about twenty minutes – and both of us had been airing our opinions freely – when I finally said to him that I was going to turn my tape recorder on and start the interview. He looked a bit surprised and said that he thought I had begun recording at the beginning. I replied that I would never record anyone without letting them know, and that I thought perhaps what we were talking about might be things that he wouldn’t want on the record.

I asked him a couple of weeks ago if he would be willing to sit down and discuss his career in the arts and politics to date, and he readily agreed. We finally managed to sync our schedules for Friday afternoon, the 26th of February, and we got together at the Second Cup in the Killam Library at Dalhousie for a wide-ranging conversation about arts, culture, the creative economy, and politics. We had actually been chatting for about twenty minutes – and both of us had been airing our opinions freely – when I finally said to him that I was going to turn my tape recorder on and start the interview. He looked a bit surprised and said that he thought I had begun recording at the beginning. I replied that I would never record anyone without letting them know, and that I thought perhaps what we were talking about might be things that he wouldn’t want on the record.

Gregor laughed. “Screw it,” he said. “Roll the tape!”

So I did.

Here is the conversation that followed – Gregor Ash… unplugged.

![]()

Paul: Okay, let’s jump right in with the NDP government here in Nova Scotia that was in power from 2009 until 2013. They did a lot of good things for arts and culture and the creative economy, but they never really seemed to get any credit for it. Why do you think that is the case?

Gregor: The issue was communication. As an example, there were a number of us working behind the scenes leading up to and before the election in 2013, trying to get some specific statements clarifying the intent – I think that if we had gotten those out earlier it would have been clearer for people in terms of what was being done in this area. In a four year period we got the return of Arts Nova Scotia. We got Status of the Artist legislation, which I felt was critical because it established a vision statement for the Province in terms of the role of artists and the value of arts and culture in society. We got Film and Creative Industries Nova Scotia. I recognized, as did many others, that we could do with the other cultural industries what we had done with film and television, and it could all come under one roof. We got so many things accomplished in the four years the NDP was in government. Despite not getting some of the other things that I think we all would have liked to have seen, those were pretty damn big accomplishments. So yeah, I was pretty proud of our record. But was it communicated? No, not so well. And so here we are now, talking about the post film-tax credit world in Nova Scotia.

Paul: What did you think about the loss of those things – the tax credit, Film and Creative Industries, the equity investments?

Gregor: I worked with ACOA and the Province and others over almost twenty years on cultural policy development and valuating the contribution to GDP and the economic value of culture in Nova Scotia and Atlantic Canada and getting those numbers. So the data was there. I recognized that the equity investment and the programs that we had for film and the tax credit were really effective. It was like Can Con for music back in the 1970s – they helped build an industry that, regardless of whose numbers you’re using, hit far above its weight. I went to Cannes, I went to LA, I went to Toronto, I was an advocate in the market, working either with government or through the film festival or with producers, selling this wonderful province and the incredible resources that we had, which was supported by the tax credit. We had great crews, we had really great actors and directors and writers. We had all of the resources here in this small little place, a two and a half hour flight from Toronto. And what an industry it created here. At the film festival, for example, we established Strategic Partners, which was all about the talent and the resources that we had here. We could connect Nova Scotia and Atlantic Canada with the rest of the world. To find creative ways to finance a film so that you could get it done by going out and having leverage in the marketplace based on what we could offer. Hollywood controls the film industry. Having tools that allowed us to go there and say, “look, we’re an attractive place, we can more than do the job, and the tax credit makes it an easy proposition for you,” particularly in times when the dollar differential wasn’t there.

And then there was the equity investment program, which was really all about telling our own stories. This was investment in Nova Scotia filmmaking – Nova Scotia writers, Nova Scotia actors, Nova Scotia directors, telling our stories, not someone else’s. It was more than just about return on investment. And now it’s gone.

I worked with previous governments. I worked with John Hamm’s administration, I worked with Rodney MacDonald and John Savage when they were in power, and of course the Dexter government. There were ups and downs, but they always understood the value of the industry. If I look at who was an advocate for the film industry, for example, we never had a bigger advocate than John Hamm. That trip to LA where he went down, that was at a time when we were scrapping for every bit of production that we could get. He didn’t just go down as a talking head on a free trip to LA – he knew about the industry. He was a film lover. He used to sneak in at the festival after the official things and line up like everyone else. He refused free tickets. He just wanted to see films. And most people didn’t know he did that.

Paul: You were in the music industry in the 1990s before you moved into the film industry. Those two industries have significantly different funding models in terms of how they disperse government monies – the film industry has always used programs where any decisions that had to be made in terms of investment were made by the civil servants and government agencies that administered them, whereas groups like Arts Nova Scotia have used a juried system, where an applicant’s peers get to decide whether or not they receive money. I’ve always felt that the former is by far the better and more equitable system for film – I’m curious which one you favour.

Gregor: Film was always different than the other creative industries because you’re talking about very complex, high cost projects. This was bringing a crew of forty-five people together with talent, that leveraging investments and different layers of funding, so it is more complex and carries with it a bigger requirement for certainty and stability.

Paul: My view as program administrator of the equity fund was that I never read scripts, at least not as part of the adjudication process.

Gregor: And you shouldn’t have.

Paul: Because my job was to just look at the business case; it was up to the private sector, whether a broadcaster or a distributor, to determine whether the creative worked.

Gregor: Right. There’s your trigger. I always thought that publishing and music could benefit from similar programs that were input – output. A film is something seeking an audience. The Americans do that really well – they figure out who the audience is, and they make lots of gambles on projects, knowing that one or two are going to kind of cover the book for everyone else. If you had the Rosetta Stone of what was going to be a hit film, you wouldn’t be working at Telefilm or any of the provincial agencies – you would be sitting on a platinum throne in Hollywood dispensing wisdom because you could always pick winners. That said, it’s risk, and if a distributor or a broadcaster or one of these other channels of money was saying, “hey, I’m in for X amount of dollars,” there’s your trigger, and it should be pretty black and white. Music, publishing, they didn’t have these kinds of programs with the same level of complexity, so having them delivered through Music Nova Scotia or Arts Nova Scotia was more appropriate. In film, the numbers were bigger, and there were more people involved.

Paul: So if you were King of the Nova Scotia arts funding system, if you had a platinum throne, which department would you have in charge of all of these funds? Communities, Culture and Heritage? Business? Finance?

Gregor: Again, tax credits are one of those things that should be pretty black and white, so have them administered by the people who know numbers. I’ve always said that tax credits should be input-output. If you pre-qualify, you’ve got certainty. So the whole thing with the Digital Media Tax Credit, for example, is that you have rules and if they are told that they qualify for it then that should be pre-qualification, right? So then it’s just a question of making sure that whatever the eligible expenses were are there at the end. It should be done in a timely enough manner that you’re not putting undue pressure on that business to cash-flow the amount of the tax credit, because that gap financing has interest accruing on it and so if someone in government takes an extra six or twelve months to process a credit government doesn’t pay a cent on that, but that business is carrying the load on that.

Paul: Should the government be spending more on arts funding, and on the creative economy?

Gregor: This is about our arts, our culture, our stories, the things that we think have value beyond straight return on investment. I can talk about the fact that Nova Scotians spend more on arts than they do on sports, and yet we tend to have more hype about sports.

Paul: Interesting point.

Gregor: Yeah. When was the last time we had a real performing arts centre on the table? Not a 2,500 seat big venue, which may or may not be viable downstream, but when we talk about arts infrastructure we always talk about it in conjunction with other things. So yeah, I would have struck really hard to double the arts budget. It’s roughly around $13 million on a $10 billion budget – it’s basically been the same amount for ten years. Rodney MacDonald, give him credit, increased the budget by about a million, the NDP then increased it by a little bit, and then there was some moving around amongst programs, but it’s long overdue for a true doubling of that amount. I do a lot with STEM now, and all the talk is about “Stem to steam” – putting art into science and technology and engineering. It’s recognizing how integral arts and culture is to our society. When a doctor becomes really good at surgery, for example, they call it an art. So yeah, I would have doubled the budget, because it’s important.

Paul: Let’s switch tack a bit and talk about your time at the Atlantic Film Festival. You were there for a long time.

Gregor: Sixteen years.

Paul: Talk about how and why you got involved in the festival in the first place.

Gregor: I’ve always been a big film fan. I grew up in Clarenville, Newfoundland, about two hours north of St. John’s, and we saw films Sunday afternoon at the Caribou Lounge on a 16 mm projector – films like Empire of the Ants, and Ben – and through high school I would stay up late watching kung fu movies, The Cat’s Pajamas, all sorts of stuff. I always went to the theater by myself – we had a one screen theater in the town where I went to high school in Ontario – and then when I lived in Vancouver I volunteered at the Vancouver festival, which was quite small back then. Then when I moved to Halifax, I started volunteering at the Atlantic Film Festival. There’s a picture of when the offices in the old NFB burnt down, and everyone is looking on, and I can see Lee Anne Gillan, and Lia Rinaldo, and I know that I’m two heads behind and out of frame. So I had volunteered at festivals for a long time, and when I made the decision not to be a music rep anymore I took the summer off and sold t-shirts on the Halifax waterfront…

Paul: Let’s back up just a bit. Tell me about your time in the music industry at the height of the Halifax “pop explosion” in the 1990s.

Gregor: I worked with CKDU, I worked with Cinnamon Toast Records, managed some bands and stuff, and then I was a music rep for about three years, first with Denon Records and then with Fusion. Then I decided that I didn’t want to do it anymore. I got this job with A & M, and I had gone from representing some of the most amazing labels on the planet – Arhoolie, Bullseye Blues, Rykodisc, Flying Fish, Tommy Boy – you know, great world beat, jazz, folk. And I had the hardest time selling stuff. I would go into Sam’s on Barrington and see the other guys racking up five hundred copies of a single album and I was selling one or two, maybe five on a good day. In fact, aside from Coolio’s first album my best-selling album was by Ali Farka Touré and Ry Cooder. Anyway, I took the job with A & M and sat down with the regional sales manager and was told how I had to go in to every record store in Atlantic Canada and front rack the new Boyz II Men album, and it was that last album before they disappeared, and I remember listening to it and thinking, “I don’t like this at all.” So I quit. Gave my notice, and didn’t know what I was going to do, so I sold t-shirts on the Halifax waterfront and sold most of my CD collection to Dischord to pay the bills. Then someone told me one day that the Atlantic Film Festival needed a person to sell ads, and when I had worked at CKDU I had done some ad sales, so I started at the festival selling ads, and I made more selling ads in two weeks than almost every other staff person was making for their entire contract. Anyway, I was going in to get my cheque and someone who was supposed to start doing transport and guest reservations had gotten a job on a film, so the executive director, Robin Johnston, asked me if I knew anyone who could do it, and I said, “me.” So I started working for the Film Festival and had a great time. Then Robin announced that she was stepping down afterwards, and I applied for the job of executive director. Got interviewed, was in the top three, but didn’t get it – a wonderful guy named Gord Whittaker did. Just after he got the job, Gord called me up and asked if I wanted to come on board and do operations. I said yes, and that’s how I started out at the Atlantic Film Festival. I was the operations guy. During the Festival, I was the guy who would hang out with all the post processing guys, guys like Steve Mayhew and Ed Higginson. I was also driving all the filmmakers around because sometimes it was tough to get enough volunteers and we didn’t have paid staff back then. And I also volunteered at Word on the Street – I used to run the main stage. The Festival was so hectic every year that in the closing days I would go from driving people to the airport for the Festival into the morning, then give the keys to the van to someone else at about 8 o’clock in the morning, then head down to Word on the Street, where I ran the main stage as a volunteer, run the main stage, then give my clipboard to someone to wrap it up, and then get back in the Festival van to finish driving into the night.

Paul: [Laughs] I’m not sure I would have wanted to been in the van with you on the nighttime shift!

Gregor: [Laughs] I know! But that was the excitement of the Festival back then.

Paul: So when Gord left a couple of years later, you took over.

Gregor: Yes. Gord was there for two and a half to three years, and I applied for the executive director job again after he left, got it, and eventually wound up as the longest serving executive director in the Festival’s history.

Paul: What was your vision as executive director? What were you trying to create?

Gregor: The Atlantic Film Festival had always had a reputation as a filmmaker’s festival. By the time I took over it was in transition in terms of balance between national and international and regional focus, because we always had the sense that it could be a bigger player. It was already hitting above its weight. It struggled with resources, so part of the plan was to increase sponsorship, to communicate better to government the role that we were playing and the impact we were having so that they would increase funding, and to create a more consistent product. We wanted to be able to attract better films by the kind of filmmakers that the local filmmakers wanted to be rubbing elbows with and the distributors that they wanted to see their films. Which is why the Festival launched Strategic Partners, which is an international business conference. When I took over the festival the cash budget was a little less than $300,000, and the full budget with in-kind was around $500,000; when I left the cash and in-kind budget was about $3 million. We went from two and a half staff to twenty-one full-time, year round staff, along with upwards of seventy part-time. At a certain point we brought in a focus on music as well, because music is always such an important part of the film, but was usually neglected at film festivals. When I was part of the music scene we had the Halifax Pop Explosion at the same time as the Film Festival, and I remember going to a Film Festival event one evening and there was Bruce MacCulloch, and then there he was the next morning at the 7” vinyl fair at the Pop Explosion plunking down a hundred and fifty bucks on records. So the vision was to create this destination event, after the noise of Toronto where it was all about the numbers and the game, that could be an oasis about community and connection all while trying to do the best job to present local films alongside international films.

Paul: That’s a tricky balancing act, isn’t it?

Gregor: Hugely tricky. On the one hand, there’s a built in audience for the regional films, particularly the stuff that comes from Halifax. But while being in NS with the largest number of submissions we had to strike a balance – under-represent one province in a given year and we’d have to deal with letters to our funders who would then make threats of a decrease in support because of an imbalance in films. You talk to the sponsors, who are paying fifty per cent of the entire ticket, and they ask things like, “why don’t you have Egoyan’s new film opening the Festival.” Well, because some little prick at Alliance Atlantis who is playing god with his interpretation of distribution, has made a decision that the Atlantic Film Festival is not going to get any of these big name Canadian films because it’s going to be the entire audience for that film in this market. To which I would say, “hey, wait a minute – weren’t you paid a distribution fee by Telefilm Canada?” Part of the funding model for film festivals was about creating excitement and hype about these films.

Paul: That’s pretty short-sighted by the distributor.

Gregor: Yeah. So it was always a sort of a balance, and we played that balance and did the best we could. We were at the whim of funding, and we were at the whim of the audience. Every year we would put together a plan and then go out and try and sell that plan, and raise the money knowing that most of the funding that you were going to get was going to be activated over ten days when the box office opened. So in terms of cash flow, it was always a challenge. And then 2008 hit with the worldwide market crash, and in one year we had a thirty-three per cent drop in our sponsorships. Over $240,000 in sponsorships disappeared in one year, yet we had the commitment to do all the parts of the show. Times were tough, and we struggled to maintain the budget and keep it balanced.

Paul: Did you ever consider walking away at that time?

Gregor: I look back at my career as of 2008, because at that point I had been executive director for almost a decade, and I had met all my goals. There were highs and lows, but I had worked with an incredible team, who had as much or more to do with the sucess as I did, and we had launched Viewfinders, and we had launched Al Fresco – we had year round activity. We had challenges, and thank God for people like Ken MacIntosh and Nan MacDonald at the Royal Bank who understood the value of the Festival and were very good with helping with some of those perpetual cash flow issues. I can safely say that there would have been no Atlantic Film Festival without the Royal Bank and those two people. But 2008 was tough. I made a decision then that I somewhat regret, and that was the decision to stay on. From 2009 until 2012, my heart wasn’t necessarily in it. I stayed on because I was committed to the Festival… [pauses] And I was fearful of what was next. I knew the realities that the Festival was facing, and I had a hard time dealing with those. The Festival was more than numbers on a balance sheet to me. It was more than ten days in September. It was the lives and aspirations of filmmakers, and the twenty or so people we employed who contributed far above and beyond what they were expected to do. Was it perfect? No. But I think we did a good job. We created something that was the envy of other festivals. As hard as it was in those later years to keep going, when you got to the ten days of the Festival you were reminded of why you did it. But it is something that I think about a lot, because it taught me a lesson in terms of knowing your “best before” date and seeing the signs that are on the wall. There were things that I probably still did well at the Festival, but there were also things that I didn’t. That was probably the three hardest years of my entire life. But all that said, we still put on an amazing event.

Paul: What do you think of the job that the current executive director and staff are doing at the Festival?

Gregor: Wayne Carter had to come in and do a hard job. He was the one who had to sit down and look at the numbers and figure out how to make things work. If I had done my job better I probably could have prepared things a little better for when he took over. I don’t know. But the times were different. We had the luxury to grow and to make certain decisions and keep people on. I told the board of directors when I was hired that I wasn’t interested in coming in and creating a bunch of arts jobs where people did all of this work for forty cents on the dollar. These were professionals. My goal was to raise the money to make sure we were able to provide things like a decent wage and a health plan, so we could have more full-time staff and provide a more consistent and professional product. When the market crashed it became harder and harder. Digital technology changed things too, as did Netflix. Suddenly there were festivals all over the place. When I left we were negotiating with Empire Cinemas around taking ownership of the Oxford Theatre, and part of those negotiations were around what we could and couldn’t show. A lot of it was down to the fact that things that were previously deemed repertory cinema were now coming over to the mainstream. Slumdog Millionaire was one of the examples. That would have come out as a rep cinema product but transitioned over into monster box office.

Paul: So is there still a place for the Atlantic Film Festival given the changes in the economy and in technology and with the proliferation of smaller local festivals like the Halifax Independent Filmmakers Festival or like the ones in Truro and Parrsboro?

Gregor: Yeah – every Tom, Dick and Harry now has a film festival. That was one of the last things I was working on at the Festival – a new strategic plan. You had this perfect storm of decreasing revenues, decreasing government funding, a proliferation of new technology and channels that allowed people to more easily see films that had been exclusive to the Festival, and because of that you had festivals popping up all over the place. We used to make the joke that you could put two films together, put them on a Friday night, and all of a sudden you were a film festival. And here we were struggling to go to people like this arsewipe at Alliance Atlantis who sat on his throne and dictated which Canadian film festivals could get Canadian films, and then we had to answer to filmmakers and audiences as to why we didn’t have those films. It was a struggle. Any organization that grows at some point tips the balance in terms of the original vision it had and the realities of trying to implement that vision. So now the world has changed. What do audiences want? The Festival was always an experience-based event and I don’t know how, without the resources, how you deliver that experience anymore. Now we’re getting simultaneous streaming, DVD and theatrical release. How does the Festival compete in that world? You’ve got mainstream cinema that because of technology can program in that rep film for two screenings. So the Festival has to be about the experience, but that takes resources and planning. I don’t envy them. Maybe it’s time to get back to being a filmmakers’ event. But now that’s even tougher. One of the last arguments that we used to have in our favour in terms of some of the funding that we had was the fact that government supported the value of the film industry and film community. Nova Scotia within Atlantic Canada was the most prominent player, and within Canada we always jockeyed back and forth between fourth and fifth in terms of largest production centers. Now that infrastructure is gone, and with it companies like SIM, PS Atlantic and Kodak, that sponsored the Festival. Are they still going to sponsor it? I don’t know. So now you have a further erosion of the foundation that supported it. And like the film industry itself that is struggling to get back to where it was, the government going out and saying that the industry doesn’t have the value it always claimed it had erodes confidence in general. So the Film Festival has to go out and pitch a product, and one of your biggest advocates has basically undermined the value of what you’re trying to sell people on.

Paul: Is part of the problem maybe that the support from the federal government has become half-hearted as well? We haven’t had a full-time regional director for Telefilm for years now, as just one example. What kind of signal has that sent?

Gregor: Yeah, I think taking the regional director out and weakening the regional presence in general was definitely a blow. My guess is that Telefilm is still there for roughly the same level of sponsorship for the Festival, but the question remains – what is their actual presence in the community? I remember having meetings in Montreal with Telefilm and we talked about it then. There were similar roundtables at the Film Festival where we would talk about distribution, and I blame Telefilm to a large degree. We were being funded as a promotion venue for Canadian films. So Telefilm was funding us to program these films, then we were going to the Canadian distributors who were making arbitrary decisions about what we could show and were also charging us $2,500 plus 50% of our gross take at the box office. So do the math. We’re getting money from Telefilm to program Canadian films, that we’re then giving a lot of that money to a distributor who had gotten money from Telefilm to distribute that film. [pauses] That’s a big “fuck you” to us.

Paul: What a racket.

Gregor: Yeah. [Laughs] This is like a therapy session now!

Paul: I don’t think a lot of people understand, even within the industry, how this all works, so they wonder why they can’t see the films that they want to see or that are made in Canada sometimes. Switching tack slightly, what are your thoughts on Canadian films in general in terms of finding an audience? How do we compete with superhero films and blockbusters from south of the border that take up so much space in our theaters?

Gregor: As executive director of the Atlantic Film Festival, one of the things that I did was take an active role in film policy advocacy, and this was a major focus of the conversations that we all had over two decades. It’s tough. But when you develop a product, you need to think about who your audience is going to be. And a lot of film in Canada was developed where they start thinking about audience after, not before. Having a strategy to get the audience is something that you need to have in the can before you start filming. But we’ve been retro-fitting strategies and resources for finding an audience after the film is made. We need to put more support and develop better methodologies and tools to support the filmmaker and the film in audience development, because the competition has never been greater.

Paul: Do we obsess too much in this digital age with a theatrical release as a mark of success?

Gregor: Yes, because the channels are everywhere now. I have two cell phones. Both have high definition screens. If it’s not a film that requires a big screen, like a film with a lot of special effects, then I don’t mind watching it on a small screen like that. I can still appreciate the craft because the fidelity is still good. But you have to make it easy for people to find it too. The CBC’s digital platform, for example, is terrible – it can take you twenty minutes to find something. [Pauses] You know, the CBC played a crucial role in developing the industry down here. Viewfinders was started because of support from both Penny Longley and Fred Mattocks at CBC Maritimes. But the fact that we have lost so many resources from the CBC down here in the last several years has been a real setback as well. We need to re-commit to the CBC as a country, but a CBC for tomorrow, and not for yesterday. I think a critical part of that is the role that they have always played in telling Canadian stories, and giving people a place to see those stories. We tell great stories, and if you get 600,000 people watching it on the CBC that’s pretty damn good box office.

Paul: Last subject. You’ve always been heavily involved in politics as a supporter of the NDP. You ran in Halifax Chebucto in the 2013 provincial election, but you also ran in the 2011 federal election against Geoff Regan in Halifax West, and I remember that there was about a forty-five minute time period that night where the media had called that election for you, and it looked like you were going to be a Member of Parliament… and then it all changed. What was that experience like?

Gregor: That campaign was amazing, and it was brilliantly run. I put in a year on the ground before that. Geoff is a good guy, and I think he’s going to be a really good Speaker now in Parliament, but Geoff wasn’t very present in the riding at that point in 2011 and hadn’t been for a while. I heard that at the doors as I went around the riding campaigning, so it was believable on election night when they announced that I had won that I had really gotten it. But it was also a suspension of disbelief. I had a lot of support, particularly from my family, and if it hadn’t been for the advance poll, who knows. I enjoyed every second of that federal election. Contrast that with the 2013 provincial election, which was really hard on my family. It was really personal, dirty, tough. But I’m a realist. Politics is a game. You like to think that you’re out there talking about values and people are responding to that, but a lot of it is about money, a lot of it is about name recognition, and a lot of it is about luck. I’ve been part of the tide coming in, and I’ve been part of the tide going out, and it’s great when you’re on the tide coming in and it sucks when you’re on the tide going out, no pun intended. It’s a tough game.

Paul: Do you think you’ll ever run again?

Gregor: I’m a political animal, so I probably will come back at some point, but I think that if I come back it has to be with a sense of realism. The thing about the provincial campaign – and the federal one – is that I campaigned on values. I didn’t bad-mouth my opponents, I talked about myself, my history, my values, I answered a lot of questions about the government in power, but you realize at a certain point that there’s a lot of chance and a lot of circumstance involved. Talk to Andy Fillmore. He put in hard, hard work, and no-one thought he was going to beat Megan Leslie, and now he’s in. This is the reality of politics. I look at organization and structure and the game of politics now and you look down south and that’s a game that’s traveled north. The infrastructure of running political machines, and the packaged marketing messaging, and the value massaging, versus the values themselves – it’s a thing that I struggle with. But I’m a student of Machiavelli – politics is this game of thrust and parry, and I forgot it during my two election runs.

Paul: [Laughs] I didn’t think there were any students of Machiavelli in the NDP!

Gregor: [Laughs] Hey, I’m a social democrat but I’m also a realist. I always know that there’s a possibility to win, and there’s a possibility to lose, and that’s the hardest thing that candidates go through, because they all believe that they’re going to win.

Paul: Did losing hurt?

Gregor: I’ll tell you the moment that was really devastating. In the provincial election everyone was saying, “oh, you’re going to win” and the response at the doors had been really good, but we just weren’t getting the commitments. So I had a feeling it wasn’t going to happen, and it didn’t. But then the day after the election few volunteers showed up. So I got in the car with my son, and we went around and picked up my signs. And my son turned to me, choked up, and said, “I’m sorry, Dad, I should have helped you more.” [Pauses] Everything else is water off the back. You live by the sword, you die by the sword. But having my son turn to me in the car and say that… I was floored. But will I run again? Sure. [Pauses, smiles] Don’t know where, don’t know when… but someday.

Paul Andrew Kimball

Latest posts by Paul Andrew Kimball (see all)

- McNeil Government’s Culture Action Plan – All Talk, No Action - February 23, 2017

- “First Features” Film Series Begins at Dalhousie Art Gallery - January 17, 2017

- View 902 Podcast Episode 3 – Silver Donald Cameron - January 5, 2017