Lance Woolaver Launches Full-Length Maud Lewis Biography

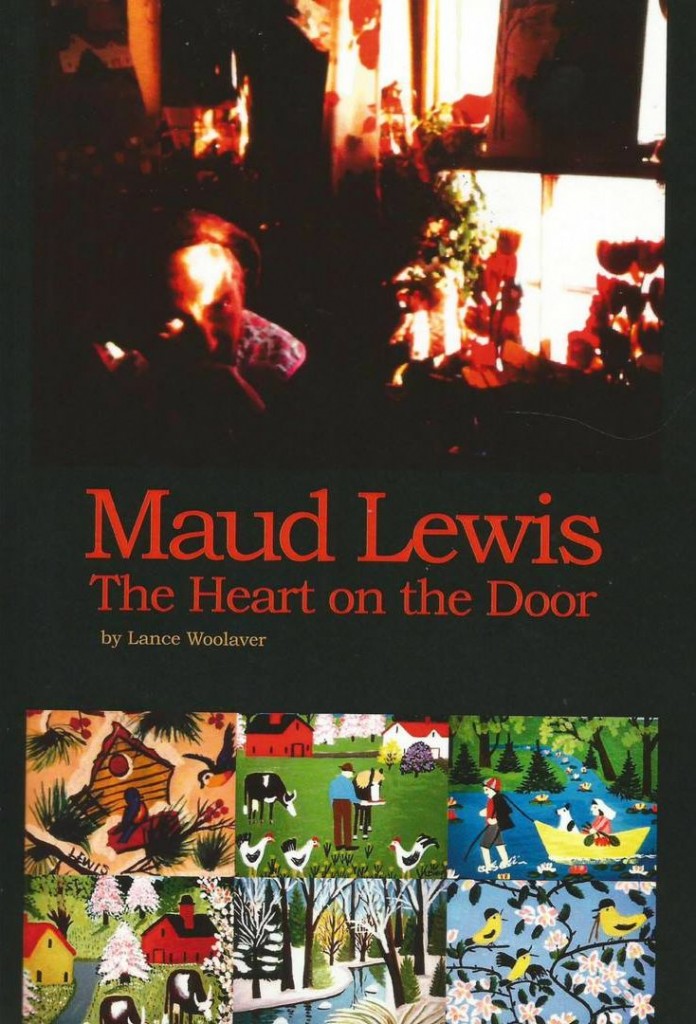

Friday, October 14th, 2016 witnessed the official launch at Zwicker’s Gallery in Halifax of Maud Lewis: The Heart On the Door, Lance Woolaver’s comprehensive new biography of Nova Scotian folk artist Maud Lewis.

Friday, October 14th, 2016 witnessed the official launch at Zwicker’s Gallery in Halifax of Maud Lewis: The Heart On the Door, Lance Woolaver’s comprehensive new biography of Nova Scotian folk artist Maud Lewis.

Woolaver’s book is the culmination of a lifetime’s work on the subject. More than two decades of research went into this landmark 450 page tome. He grew up near Maud Lewis’s house, and his father, Judge Philip Woolaver, was one of the legendary folk artist’s two patrons (the other was her physician).

With the release of the Newfoundland / Irish feature film co-production Maudie this year, interest in the life and work of Maud Lewis is cresting again. Fifteen years ago, a national tour of her paintings, along with the publication of the best-selling coffee-table book The Illuminated Life of Maud Lewis by Woolaver and Bob Brooks, and sellout performances of Woolaver’s play on the same subject, brought the iconic folk artist’s work to national and international audiences. The new feature film and Woolaver’s indicate a further revival is underway.

While the film sugar-coats many aspects of Maud Lewis’s difficult life (no doubt a necessity for a commercial release), Woolaver’s book dives in and brings available light to the painter’s true lifelong sufferings. That she managed to concoct such bright and cheerful paintings under such dire social and personal conditions is something of a miracle.

While the film works hard to humanize her husband Everett, portrayed by the great actor Ethan Hawke in a vivid performance, the facts of the story, laid out in Woolaver’s book, are simply horrifying.

Woolaver, in his introductory remarks at the book launch, was unflinching. He calls it a ‘very dark book’. Heartbreaking, in fact. I know some of it from our research together on the Digby Poor Farm, where Everett was interred and where he eventually became the night watchman.

The history of Nova Scotia’s Poor Farms and Poor Houses lasted up until the very late 1950s. The system, dating from the Elizabethan Poor Law from 1601, dictated that poverty was a parish or municipal responsibility, governed by a poll tax. If you could not pay your poll tax, you were interred in the Poor House or Poor Farm, with no way to get out (until you were buried in an unmarked grave, that is).

Concerted efforts by the Progressive Conservative governments of Robert Stanfield and John Diefenbaker at the provincial and federal levels, respectively, dismantled the system, replacing it with a province-wide welfare program.

Up until then, however, the existence of the Poor House gave full force to the phrase “you’re going to send me to the Poor House!” It was real, and the fear of ending up there was a dark spectre that haunted countless Nova Scotians.

Woolaver stated in his remarks that this was the real fear of Maud Lewis in the late 1930s. The offspring of a well-heeled family in Yarmouth, where her family owned the local cinema and a jazz nightclub, Lewis devolved downward into poverty when her brother inherited, and then squandered, the family’s finances.

Once her eldery aunt, with whom Maud was living, entered a period of frail health, Maud Dowley was forced to seek out employment and living quarters. She found it by answering Everett Lewis’s ad for a live-in housekeeper.

And while the film suggests that Maud Lewis eventually tamed Everett’s crude ways, suggesting a loving marriage and an almost happy ending before the painter’s ongoing health problems eventually overwhelmed her, Woolaver’s research indicates that happiness may have only ever emerged in the startlingly beautiful paintings Maud crafted, rather than in her life itself.

The folksy prose of the book, delivered in an almost sing-song like style, helps to lighten the dark content of the story. Woolaver manages, through sheer force of detail, to bring back a part of Nova Scotia’s history that almost nobody wants to remember.

When we were working on radio documentaries about the Poor Houses, we consistently came up against an unwillingness by many to deal with such awful memories. The history of poverty in Nova Scotia gets even worse the further back you go. Before the Poor Farms and Poor Houses, there were the Poor Auctions where the people were auctioned off as free labour. No wonder no one wants to remember.

Woolaver pitched the Maud Lewis story to several Nova Scotia film production companies, to little response. Perhaps the story found more resonance in Newfoundland, where the entire colony went bankrupt in the 1930s. The fact that the film was shot in Newfoundland reflects the necessities of utilitsing that Province’s tax credit system; alas, the lush confines of Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Basin area were not visualized in the film, replaced by barren yet hauntingly beautiful Newfoundland landscape that give an entirely different flavour to the story,. In the end, perhaps it’s fitting as a metaphor for Maud Lewis’s life.

Lance Woolaver’s Maud Lewis: The Heart On the Door is available at Bookmark on Spring Garden Road in Halifax and through Amazon.

Ron Foley Macdonald

Latest posts by Ron Foley Macdonald (see all)

- Mary Tyler Moore in Nova Scotia - January 30, 2017

- Viola Desmond’s Story on Film - December 11, 2016

- Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” - December 9, 2016