Nova Scotia’s “Titanic” Filmmaking Legacy

Last month’s column on Nova Scotia’s Oscar connections generated some interesting discussion, particularly in the case of James Cameron’s 1997 epic Titanic. Most people don’t know that one-third of that motion picture was filmed in Halifax, and that the original ten-day shoot turned into a three month marathon.

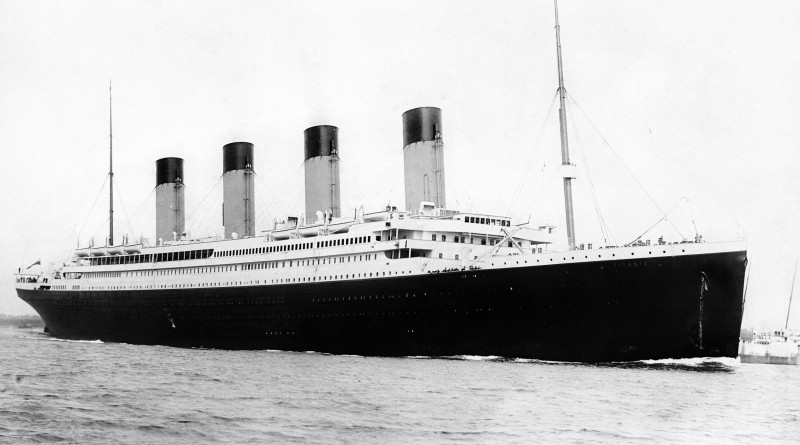

If you don’t think the saga of RMS Titanic is at least in part a Nova Scotia story, the reaction to the event’s 100th anniversary, held around April 12th, 2012, certainly should have convinced you otherwise. The Atlantic Film Festival, for example, held four standing-room only screenings of non-Cameron Titanic-related films: the 1953 Hollywood-made Titanic, which won the Academy Award for Writing Original Screenplay; the 1943 German-made Titanic, commissioned by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joeseph Goebbels, who later banned it; The Unsinkable Molly Brown, a fictionalized account of Margaret Brown, who survived the sinking of the Titanic; and the 1958 British-made classic A Night To Remember, which most critics regard as the most historically accurate cinematic portrayal of the disaster. There was also a lively seminar on “Titanic in the Media” which I had the pleasure to chair.

The parade of international media crews covering the anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic confirmed Halifax’s importance in the story, particularly the fact that approximately 200 victims remain buried here. While the sinking of the great ship took place in the North Atlantic in international waters, Nova Scotia’s capital was, crucially, the base of most of the recovery efforts.

Cameron’s 1997 film about the disaster utilized a Russian ship just off of Halifax harbour as the location for its Nova Scotia shoot. The parts of the film shot here made up the narrative framing device used in the film, modern-day sequences that began and ended the story with actors Bill Paxton and Gloria Stuart looking for the lost piece of jewelry that activates the rest of the story, which was of course the full-on costume drama recreation of the Titanic’s fateful voyage across the Atlantic in 1912.

Interestingly, Wikipedia’s article on the 1997 film makes no mention of Halifax or Nova Scotia. It does recount the notorious end-of-shoot incident where a disgruntled crew member spiked the closing night chowder with PCP, causing chaos and a rush to various hospitals for the cast and crew. The culprit has never been caught; actress and playwright Jennifer Overton has even written and performed a one-woman show about the night of Titanic’s infamous wrap party in Halifax.

Cameron’s epic shoot in Nova Scotia has other fascinating associations. His ex-wife, Kathryn Bigelow (the only woman to win an Oscar for Best Picture and Best Director, for The Hurt Locker), made two films in Halifax, K-19: The Widowmaker and The Weight Of Water. With only nine feature credits as a director, that means the lauded female filmmaker has made almost one-quarter of her output in Halifax.

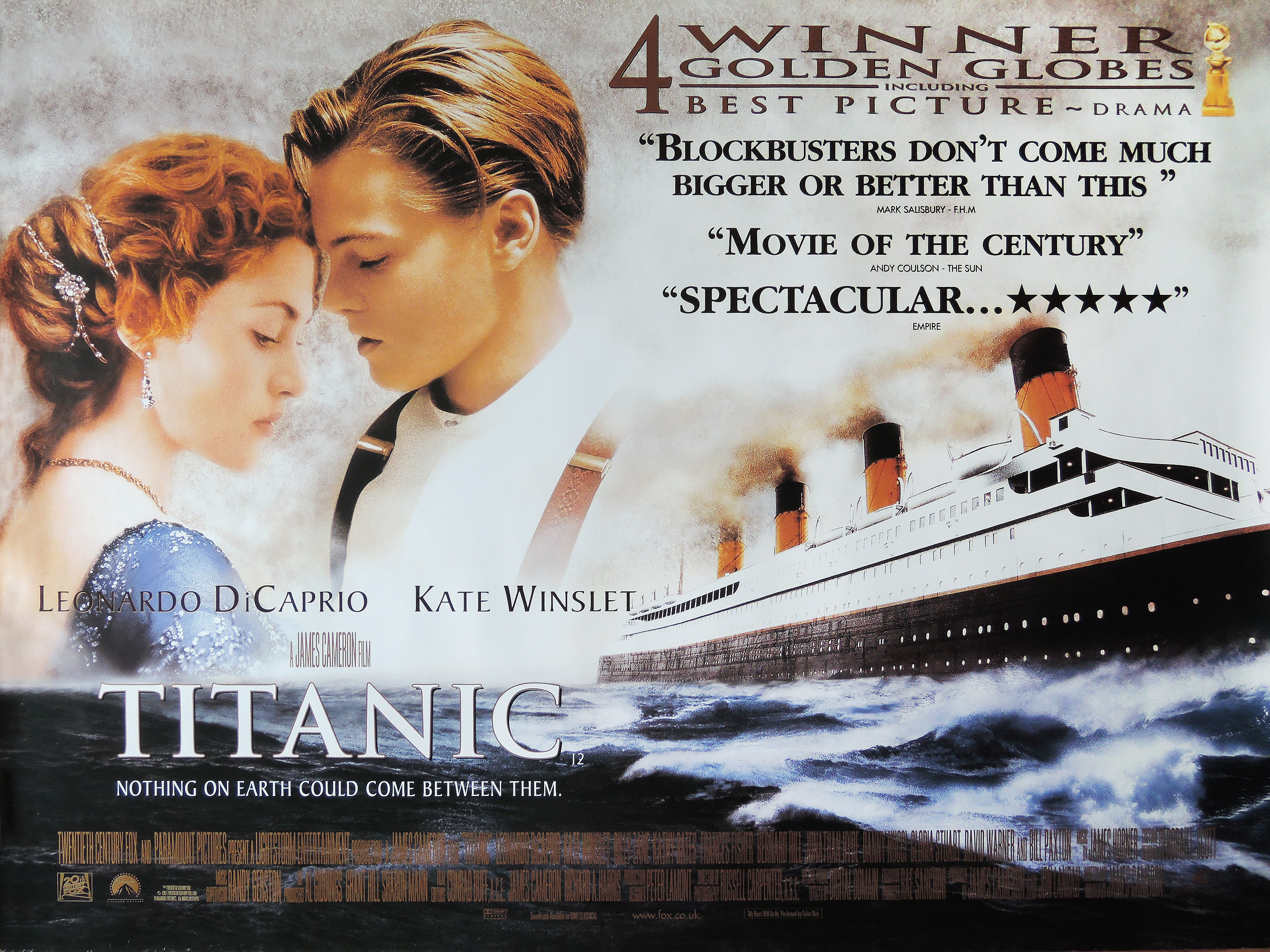

The 1997 version of Titanic rates all this attention because at the time it was both the most expensive feature film ever made (costing $200 million) and the highest grossing (over $2.1 billion in box office returns). It was nominated for 14 Academy Awards, winning 11, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Costumes, Best Original Song, Best Music, Best Editing, Best Sound, Best Visual Effects, and Best Cinematography.

From an industrial point of view, Titanic also was a tipping point in the motion picture business where computer generated imagery was seamlessly integrated into a costume drama rather than a science fiction or horror film. Filmmaking would never be the same; in fact the innovations from the Titanic would eventually lead to ‘film’ being replaced by computer hard drives, making the term ‘motion picture’ the only really correct way to describe the process by which television and features are now actually made.

James Cameron has been a consistent innovator in every one of his films, and Titanic represented an extraordinary turning point for the industry itself. His next film, Avatar, would surpass even Titanic in sheer expense and box office, but Titanic would remain a landmark in the history of motion pictures. It certainly marked a significant moment in Nova Scotia motion picture production history, along with marking a salient point for Nova Scotia’s place in the pantheon of great films.

Ron Foley Macdonald

Latest posts by Ron Foley Macdonald (see all)

- Mary Tyler Moore in Nova Scotia - January 30, 2017

- Viola Desmond’s Story on Film - December 11, 2016

- Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” - December 9, 2016

I wonder if those at the screening noticed that some of the miniature shots in the 1955 British film “A Night to Remember” were lifted from the 1943 German film “Titanic”?