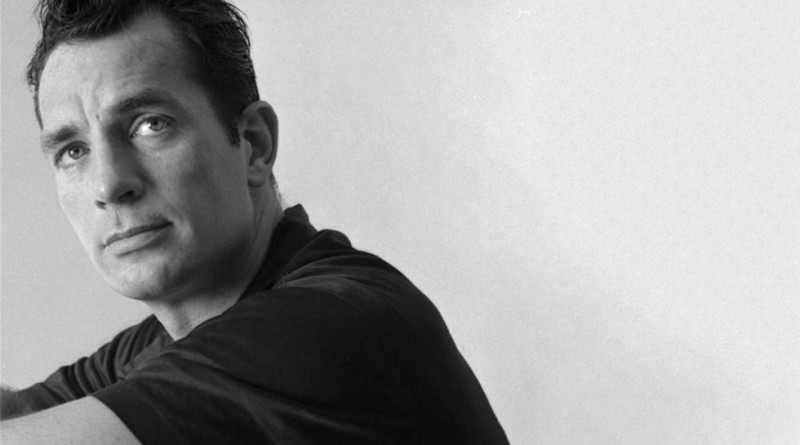

Jack Kerouac’s Maritime Connections

Jack Kerouac was a distant cousin of mine, and his life and work continue to resonate with me, even as I eagerly await another volume of uncollected works slated to be published this coming September.

Kerouac, along with Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, formed the triumvirate of literary and cultural giants at the center of the Beat Generation universe. They set the stage for the 1960s Counterculture, and a general questioning of all Western values that has lingered on into contemporary times.

Kerouac makes several references to Nova Scotia in his works. There’s one, in Tristessa, a novel set in Mexico City. There are two others that describe the same incidents when Kerouac, then a merchant mariner in the midst of World War II, landed in Sydney for a raucous shore leave that ended up in some nice working family’s living room after a wild all-night party.

That incident is recounted in Kerouac’s first published book, The Town and the City, from 1950. He and his editors misspelled Sydney as ‘Sidney’, but otherwise the descriptions ring true. The Beat novelist revisited the story again in his 1967 book, Vanity of Dulouz, where, this time, he got the spelling right.

Kerouac had joined the merchant marine after quitting Columbia University, where he had been on a football scholarship, once his career as a university sportsman was done due to an injury. Feeling like he had to contribute somehow to the war effort, he chose one of the most dangerous occupations, travelling the North Atlantic on a merchant ship.

The visit to Cape Breton was on the way to and from assignments to supply the new American air base in Thule, Greenland. After Kerouac had finished his trips to Thule and had safely returned to land, his ship was torpedoed and sunk.

Kerouac’s references to ‘the endless pine forests of Nova Scotia’ are of particular interest to me, not because we’re related, although that helps, but rather because of the particular strain of Tibetan Buddhism that eventually found its way to the Bluenose Province. That strain, known locally as Shambhala, came to Nova Scotia when its leader, Chögyam Trungpa, ‘felt something’ when flying over the East Coast.

Trungpa was a legendary figure who left Tibet as a young man in the midst of the 1959 Chinese Invasion. He founded Buddhist centers in Scotland, Spain and finally Boulder, Colorado, attracting attention and devotees as a powerful, if unorthodox, spiritual leader. His version of Buddhism seemed to include a meeting of the West and the East where spiritual quests seemed to include an unexpectedly hedonistic edge.

Meanwhile, Nova Scotia, and particularly Cape Breton, had begun to fill up with Beat and post-Beat figures such as Robert Frank, Richard Serra and Rudy Wurlitzer. Marshall McLuhan once famously said that artists where the antennae of civilization, foretelling the future. If that’s the case, then perhaps Kerouac did foretell of Nova Scotia’s possible role as some kind of promised land.

The Beat writer spent a great deal of time reaching for a curious blend of Catholicism and Buddhism, even penning several tracts that were eventually published as ‘Some of the Dharma’ and ‘The Scripture of the Golden Eternity’.

The Shambhala spiritual movement came to Halifax on Trungpa’s instructions. He apparently told his followers that they would experience a more spiritual life here because there would be a drop in their standard of living. About half the community from Boulder, Colorado, made the trip, including the organization’s archives and the publication The Shambhala Sun.

The Buddhists also established Gampo Abbey in Cape Breton where serious students can study and meditate for literally years on end with famous spiritual leaders such as Pema Chodron, one of Trungpa’s most famous disciples.

If Nova Scotia has become something of a destination for post-Beat culture, New Brunswick can boast of an important discovery in the Jack Kerouac legacy.

The poet/visual artist/playwright/filmmaker Herménégilde Chiasson, who would eventually become New Brunswick’s Lieutenant Governor, made a documentary on Kerouac in the 1980s for the National Film Board of Canada. In his research he found a previously forgotten Montreal talk-show appearance by Kerouac, in French, from 1967.

Chiasson’s film is called Jack Kerouac’s Road: A Franco – American Odyssey. The excerpts used by the Moncton-based filmmaker show a flannel-shirted Kerouac speaking a strange hillbilly patois while the TV show’s host, an urban, ultra-sophisticated Montreal-native in a fashionable suit, queries the writer about the whole ‘Beatnik’ phenomenon.

Chiasson’s film shows a completely different view of Kerouac, who didn’t speak English until he was six. With the new volume of work including translations from Kerouac’s until now unknown original work in French, Jack Kerouac’s Road is a valuable way of approaching the Beat Generation giant from a very different point of view, indeed.

Ron Foley Macdonald

Latest posts by Ron Foley Macdonald (see all)

- Mary Tyler Moore in Nova Scotia - January 30, 2017

- Viola Desmond’s Story on Film - December 11, 2016

- Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” - December 9, 2016